The Billy Sunday Snowstorm

Little Billy Sunday’s come to our town to stay

An’ drive the Devil out o’ here, an’ make him keep away.

—Charles B. Stevens

The sign on Wyoming Avenue read, “Reverend William A. Sunday, the world’s greatest evangelist, will begin his siege on Scranton, March 1, 1914. Will you join his army?” Thousands of Christians from the Pennsylvania coal region eagerly awaited what promised to be the event of the year. Adherents admired Billy Sunday for his plain talk. “You don’t thrash the devil with highfalutin words,” he liked to say. They also appreciated his energetic style. Prior to becoming an evangelist, Sunday had played baseball for the Chicago White Stockings, and he brought that athleticism to his preaching. He was often seen throwing off his jacket and hitting an out-of-the-park homerun with his imaginary bat and ball to punctuate some bit of homespun wisdom.

Preparations for the revival started a year in advance. Per Sunday’s instructions, churches organized prayer meetings, added extra choir rehearsals, increased Sunday school membership, trained congregants to “witness for Christ,” and raised money to build one of Sunday’s tabernacles.

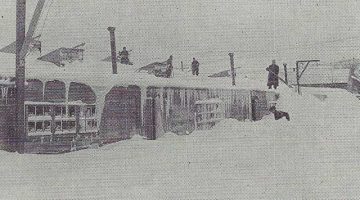

Completed on February 26th, the temporary structure could hold an audience of 10,000, plus another 1500 in the rear of the pulpit for choirs and dignitaries. From outside, the building looked like an organized shantytown, with its rough-hewn wood and abundant entrances. Windows dotted the four exterior walls and poked through the top of a turtleback roof designed to carry Sunday’s voice to every corner. Smoke curled from fifteen metal chimneys attached to the fifteen pot-bellied stoves installed to heat the main hall. Electric bulbs dangled from the rafters, lighting the seats and the sawdust-covered aisles below. Jury-rigged telephone lines and telegraph instruments surrounded the pulpit, guaranteeing quick reporting and extra editions of local newspapers.

Other preparations included newly built restrooms, first-aid stations, and a nursery at the local YWCA. “No children in arms,” according to Sunday who wanted to prevent distractions during the services. The evangelist also banned women’s hats and coughing so he could be seen and heard clearly.

It seemed Sunday planned for every eventuality except one. The weather.

March 1st began with clear skies, but as the day progressed a snowstorm moved in. The evangelist kicked off his seven-week campaign with three services that Sunday. When the evening sermon started, the streetcars were still operating thanks to plows attached to the fronts of the trolleys. While the snow accumulated outside, fourteen inches in all, Sunday continued preaching against such vices as drinking, gambling and tobacco use. Occasionally he’d have to pause and wait out the noise of the forty-five-mile-an-hour wind—“a real rip snorter,” as he called it—before continuing with his message. At one point he prayed, “God, get out there and grab that blizzard by the snout.” As always, Sunday ended the service by inviting those who wanted to be saved to come forward. He stood in front offering a “glad handshake” to anyone who “hit the sawdust trail” toward redemption.

Once everyone had the opportunity to be saved, the reality of the storm set in. All modes of public transportation had ceased with 4000 worshipers inside the tabernacle. Snowdrifts, some ten feet high, blocked roads for miles. About 1500 people who lived nearby braved the harsh conditions and walked home, but the remaining 2500 would have to “camp in the house of God,” Sunday explained. The telegraph lines were down, but as luck would have it, the direct phone lines to the Scranton Times and the Tribune Republican were still working. Sunday took up an extra collection that night, this time for food and coal. Reporters called their respective papers and arranged for patrolmen a couple miles away to deliver fifty pounds of coffee, 500 loaves of bread, and 1000 sandwiches in their wagons. Three coal company workers braved raging winds and mountainous snowdrifts to deliver fuel to the tabernacle.

According to the papers, everyone who stayed passed the night without complaint. They boiled coffee on top of the stoves in the large, concave, collection plates, and had their fill of food. The next morning, when the winds had died down, volunteers showed up at the tabernacle in horse-drawn wagons and offered rides to the stranded. After calling the storm the worst he’d ever experienced, Sunday cancelled Monday’s services and declared a day of rest.

Growing up, the story of “The Billy Sunday Snowstorm,” as it came to be known, fascinated me. When people spoke of the event, they’d insist that all 2500 inside the tabernacle had no choice but to be saved after spending the night with such a charismatic preacher. And everyone knew somebody who had been saved. Even people my parents’ age, one generation removed from the event, claimed to have known at least one person who was stranded that night. My grandmother loved to tell how she was born during “The Billy Sunday Snowstorm” while her father was “off being saved.” Scrantonians still speak about their connections to the evangelist with great pride.

When I started writing, Sing in the Morning, Cry at Night, I knew I wanted to use the Billy Sunday story but I wasn’t sure how. As it turned out, two pivotal scenes in my novel take place that evening, one at the revival and one in the snowstorm. The tabernacle may be long gone, but a century later, Billy Sunday is still causing a stir in Scranton.

References:

Bruno, Guido. “Billy Sunday, Who Makes Religion Pay.” Pearson’s Magazine. April 1917: 323–332. The Scranton Times. Various articles on Billy Sunday’s visit to Scranton. January–March 1914. The Tribune-Republican. Various articles on Billy Sunday’s visit to Scranton. January–March 1914.

Author Bio:

Barbara J. Taylor was born and raised in Scranton, PA, and teaches English in the Pocono Mountain School District. She has a master’s degree in creative writing from Wilkes University, and English and Education degrees from the University of Scranton. She still resides in “The Electric City,” two blocks away from where she grew up.

Barbara Taylor’s Sing in the Morning, Cry at Night, is being published by Kaylie Jones Books, an imprint of Akashic Books, on July 1, 2014. ($15.95, trade pb, 320pp). Visit the author’s website at barbarajtaylor.com.